A great many games are released in any given twelve month period, and there’s every chance at least a handful will be noteworthy. The tricky part is trying to quantify one game’s excellence against another, as if somehow Sprawling Open World IV is better than Too Indie For Polygons by some demonstrable metric. I can’t do it – I can’t claim that Pillars of Eternity was the best game this year.

Instead I’ll tell you how and why Pillars of Eternity made me a better person.

2015’s been a great year for role-playing, and Pillars is one of several new additions to our best PC RPGs.

In order to do that, I need to tell you a bit of backstory. Some time prior to Pillars’ release in March, I embarked on a game of Planescape: Torment. It was the blind spot in my RPG history, and the foundation of my Pile of Shame. Twelve months later I finished it, and if the game’s original developers had seen me ‘playing’ their brainchild at any point, they’d have cried into their hands.

I had no concentration span for the reams and reams of world-building text, or thousand-word dialogue exchanges. I spent the first half of the game looking at Black Isle’s remarkable writing with glassy eyes, and the second half openly skipping through it.

I didn’t mull over puzzles, I wiki’d them. If an NPC I needed to talk to during a side quest wasn’t in my immediate vicinity, I’d alt+tab right out and Google their location. Worst of all – I’m ashamed to tell you this – if I discovered that my actions had set me down a path I wasn’t completely happy with, I used a save editor to give me the item or outcome I wanted.

In essence, I played the game like a spoiled millennial brat who’s used to having everything handed to him on a plate without devoting any more attention to it than I would a Vine of someone with a haircut shouting at strangers. And I still expected the game to demonstrate its brilliance and justify its reputation under those conditions. It’s testament to Torment that it retained a sense of grandeur and importance even then, but I certainly didn’t get the intended, lauded experience.

I’m what’s wrong with videogames. I’m the reason we can’t have nice things. Why games so often play like 20-hour tutorials these days, and why titles such as Pillars of Eternity emerge as crowd-funded indie titles rather than triple-A projects: games that require real attention and concentration are a niche market.

So when Pillars turned up, I saw it not just as a videogame I might enjoy playing, but as a chance for redemption. It’s a deliberate, calculated attempt to invoke the ‘00s Infinity Engine experience, and several of Torment’s staffers brought their expertise to it. Maybe if I play this one properly, I reasoned, I’ll atone for defiling their legacy title.

So I did. I forced myself to play Pillars of Eternity in the exact opposite way to what came instinctively. I set cast-iron rules about reading prose and dialogue, and about alt+tabbing my way through quests, before hitting New Game. And as should be abundantly clear by now, it was the best gaming call I made in 2015.

(Incidentally, the second best gaming call I made in 2015 was electing to shoot a set of double-doors aimlessly with my AWP in CS:GO until miraculously headshotting an opposing player through the panel, inciting passionate claims regarding my potential use of hacks.)

I won’t dwell too much on how successfully it summons the Infinity Engine RPGs of the late nineties and early noughties, except to say it succeeds in that endeavour without ever appearing self-conscious or cloying. Only this particular team of developers could have nailed the look, feel, systems and incidental details this confidently. However, it certainly doesn’t raise the bar.

Unconventional and full of gallows humour and unseen consequences, Planescape: Torment is better written than Pillars (atleast, the bits of Torment that I actually bothered to read). That’s not a controversial statement by any stretch. But I allowed myself to enjoy Pillars’ scene-setting paragraphs and careful little details so much more, and as a result my mental map of Dyrwood and its inhabitants is that much clearer. I think back not just to the tree decorated with hanging corpses in Gilded Vale, but the creaking of the nooses as those corpses swayed gently in the breeze.

I don’t just see Durance as an ugly portrait and a health bar. I think about the way his face twitches and ticks as he talks. About the feeling of unease I always have while conversing with him, the misogynistic and pyromaniac terms he always managed to discuss grand concepts in. I’ll always remember Grieving Mother’s unsettling ability to remain unnoticed by others, even to the extent that she has virtually no conversations with other party members.

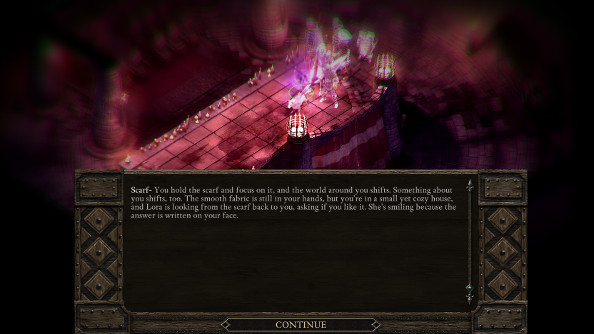

And because I bothered to pay attention to what quest givers actually said to me, not just the resultant journal entry, I found myself much more motivated to pursue them, make decisions, and live with them. At the conclusion to Lord of a Barren Land in Act I, I didn’t just pause for thought. I saved, shut the game down, and had a cup of tea while I decided what to do. RPGs are all about shades of grey these days, but Obsidian’s particularly grim Euro fantasy really made me agonise over how to leave Dyrwood in a better state than when I began.

What I didn’t factor in before I started playing is that Pillars is actually really quite difficult. Really quite keyboard-through-the-window, screaming-obscenities-at-the-sky challenging. Worse than simply chucking powerful enemies at you and forcing you to hit the pause key to have any hope of prevailing, Pillars features lasting effects of failure.

Characters have both health and endurance, the latter easily replenished by potions, spells, and foods during combat, the former only restored by resting. If someone runs out of endurance in combat, they’re knocked unconscious. However, if they run out of health, they’re gone forever.

I hadn’t devised any rules about fudging combat going in, but as the urge to search for a trainer or godmode console command set in, I realised I was faced with yet another way to dodge the full heft of a grand RPG experience. I promised myself I’d face the difficulty (normal mode, since you ask) head-on. If I had to replay areas, so be it. If characters died, they died.

Characters died.

And I had to spend the rest of the game with that on my conscience. I didn’t rest when I should have, so someone died. I didn’t use Grieving Mother’s spells correctly, so someone died. I was curious about a chest in a dungeon full of traps, so someone died. It became central to Pillars’ narrative, such that I couldn’t imagine playing through the game without those wrenching occurrences thrown in.

Its stern difficulty also forced me to go extracurricular with Pillars and scour the subreddit and forums for party guides, formations, build tips, and strategies for particular bosses or areas. And as I plumbed the undiscovered depths of Obsidian’s systems, my interest levels only heightened. There was always a payoff for doing a spot of research, thanks to the community and the complexity of the game they set up camp in.

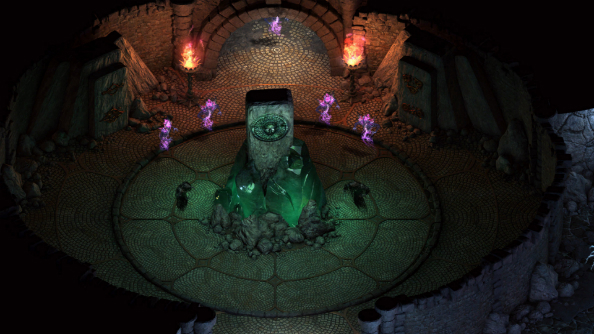

I still haven’t finished it, of course. But what a party I’ve assembled, and what an incredibly journey I’ve taken them on. Once easily bested by a single level 3 Sporeling in the caves of Anslog’s Compass, we’re now able to munch through Fampyrs, Cean Gŵlas, and Vithracks by the dozen in the Endless Paths of Caed Nua. And Pillars lets me take a lot of pride in that.

One day soon, I’ll have seen the credits roll, and will be able to say conclusively that it doesn’t have the same sense of genre-defining grandeur of Baldur’s Gate, Planescape: Torment or Neverwinter Nights (more likely I’ll equate it to the marginally less excellent Icewind Dale games). But I’d be falling into the old trap of treating games like scientific test samples to be processed and ordered into a hierarchy. What makes Pillars special to me is that it provided me with a space in which to re-learn the skills needed to play the type of game I tell people I like, and lament the scarcity of in 2015.